Honouring the Wisdom of Children: Tagore’s ‘The Post Office’

We are honoured to share a deeply evocative piece on Rabindranath Tagore’s timeless play, ‘The Post Office’ (Dak Ghar), by Indira Chowdhury, noted oral historian and founding member of the Oral History Association of India. Through the story of young Amal, whose illness confines him indoors even as his imagination soars beyond walls, Tagore captures the very essence of what palliative care strives for—to bring meaning, connection, and peace even in the face of life’s finitude. We welcome this reflection as part of our November 2025 Newsletter theme, where art, literature, and care intersect to remind us that healing often transcends cure, and that the human spirit, like Amal’s, continues to seek light beyond the window.

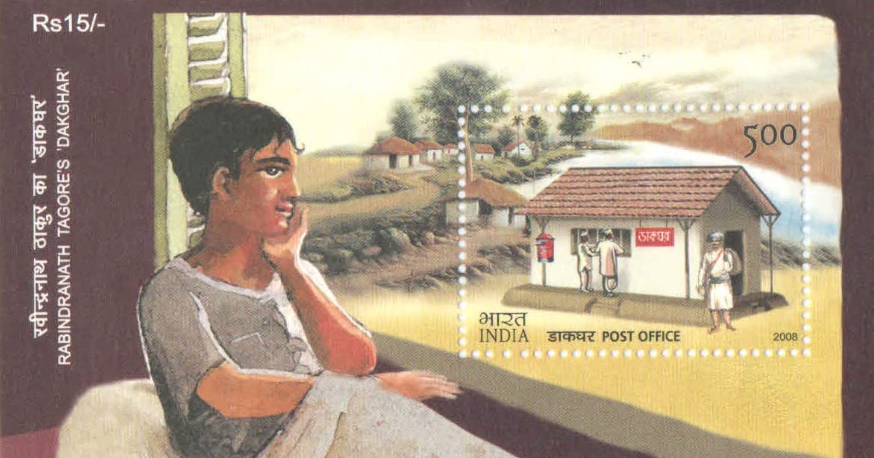

Rabindranath Tagore’s Dak Ghar (The Post Office) was originally written in 1912, a year before he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. The following year, the play was translated into English and performed at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin directed by W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory. It was performed in London that same year. Five years later, the play was performed in Bengali in Calcutta in 1917. Mahatma Gandhi had watched the play and was moved by it.

This was a play we performed quite often as children. I remember playing the hard-hearted doctor who forbade the sick child from going outdoors. My friend, now a doctor in London, was a few years younger than me and played the sick child, Amal. We would horse around a lot during rehearsals. But I recall the hush that would fall on the audience as the play reached its end.

The Post Office was written by a master story-teller who delighted in the understanding children brought to the world. It is also worth remembering that Tagore himself had experienced the tragic loss of his wife and three of his children.

The Post Office centres around a little boy Amal, who has recently been adopted by his uncle, Madhav. Amal is very unwell and his uncle has been anxiously consulting the village physician. The physician is strict and forbids the boy to go outdoors. His uncle pleads, saying it is “very hard to keep him indoors all day long.” But the physician is firm. He quotes his books saying “the autumn sun and the damp are both very bad for the little fellow.” Madhav tries again: “Your system is very, very hard for the poor boy; and he is so quiet too with all his pain and sickness. It breaks my heart to see him wince, as he takes your medicine.” The heartless physician is unmoved. “The more he winces, the surer is the effect.”

The story unfolds indoors, in the space where Amal is confined. He can only look out of a single window. Amal yearns to go outdoors but his uncle conveys to him the doctor’s orders. But through Amal’s conversation with his uncle, Tagore conveys what adults often miss about a child’s desires.

Amal asks his uncle if he could go to the courtyard where his aunt was grinding the lentils. I quote directly from the play to convey the perceptions of a child mind untainted by bookish learning:

Amal. Wish I were a squirrel!—it would be lovely. Uncle, why won’t you let me go out?

Madhav. Doctor says it’s bad for you to be out.

Amal. How can the doctor know?

Madhav. What a thing to say! The doctor reads such huge books!

Amal. Does his book-learning tell him everything?

Madhav. Of course, don’t you know!

Amal [With a sigh] Ah, I am so stupid! I don’t read books.

Madhav. Now, think of it; very, very learned people are all like you; they are never out of doors.

Amal. Really?

Madhav. No, how can they? Early and late they toil away at their books, and they’ve eyes for nothing else. Now, my little man, you are going to be learned when you grow up; and then you will stay at home and read such big books, and people will notice you and say, “he’s a wonder.”

Amal. No, no, Uncle; I beg of you—I don’t want to be learned. Ever!

… I would rather go around and see everything that there is.

Madhav. Listen to that! See! What will you see? As if there is so much to see!

Amal. Look at those that far-away hills from our window—I often long to go beyond those hills…[ Act I]

Amal’s uncle is distressed and he tries to reason with the boy. He allows him to sit by the open window and look out. From the window, Amal calls out to those who pass by. He makes friends with the curd seller – referred as “Dairyman” in the translation. In the course of their conversation, Amal tells the curd seller that he would like to learn how to tunefully cry out “Curds, nice curds – come and buy from me!” walking on the long road.

The curd seller is appalled: “Dear, dear, why should you sell curds? No, you will read big books and be learned.

Amal. No, I never want to be learned—I’ll be like you and take my curds from the village by the red road near the old banyan tree, and I will hawk it from cottage to cottage. Just how you cry out —”Curd, curd, good nice curd!” Teach me the tune, will you?

Dairyman. Dear, dear, teach you the tune; what an idea!

Amal. Please do. I love to hear it. I can’t tell you what a strange longing comes over me when I hear you cry out from the bend of that road, through the line of those trees! Do you know I feel like that when I hear the shrill cry of kites from the end of the skies?

Dairyman. Dear child, will you have some curds? Please take this.

Amal. But I have no money.

Dairyman. No, no, no, don’t talk of money! You’ll make me so happy if you eat the curd from me.

Amal. But I have wasted your time, haven’t I?

Dairyman. Not a bit; it has been no loss to me at all. You have taught me how to be happy selling curds. [Act I]

Amal’s sense of wonder and his delight in embracing the working life of the curd seller, enables the curd seller to understand what happiness might mean. It is the child who is endowed with a vision unsullied by profit and loss.

Amal meets so many people from his window – boys his age who are off to play and don’t really wish to spend time with him even though he offers them his toys to play with. They stop reluctantly but Amal is too sleepy to watch them play. He also meets the village Watchman who is amazed that the little boy is not afraid of him. “What if I march you straight to the King?” he asks. Amal replies with excitement, “Please do!” But then, he adds sadly that the doctor will not let him go anywhere.

It is the Watchman who makes Amal aware of the Post Office that he can only see from a distance and tells him that it belongs to the King perhaps, one day the King will send him a letter. Amal holds on to that hope and calls out to the Village Headman to ask if he knows anything about the letter that the King might send him. The Headman mocks him for expecting a letter from the King.

Amal also meets a little girl called Sudha who is on her way to pick flowers. He wants her to stay and chat but she has work she says. But she promises to talk to him when she is returning home with the flowers. But she is quite clear that she will give him a flower only if he can pay for it. Amal bargains for time, saying he would pay when he grows up. She agrees to this condition and promises that she will see him on her way back.

As the day passes, Amal grows weaker. Gaffer, the Fakir visits him. He says he had been the mythical Island of parrots where the birds fly freely. Immediately, Amal wants to be a bird and fly away but the Fakir reminds him: “I hear you’ve fixed up with the Curd seller to be a seller of curds when you grow up. I’m afraid such a business won’t flourish among the birds!”

Amal has questions about the Post Office.

Amal. Say, Fakir, do you know the King who has this Post Office?

Gaffer. I do; I go to him for my alms every day.

Amal. Good! When I get well, I must have my alms too from him.

Gaffer. You won’t need to ask, my dear, he’ll give it to you of his own accord.

Amal. No, I will go to his gate and sing, “Victory to thee, O King!” and dancing to the sound of my little drum, ask for alms. Won’t that be nice?

Gaffer. It would be splendid, and if you’re with me, I shall have my full share. But what’ll you ask for?

Amal. I shall say, “Make me your postman, that I may go about lantern in hand, delivering your letters from door to door. Don’t let me stay at home all day!” [Act II]

Amal just has one wish – not to be confined to his home. To be free. The doctor visits again. Amal says he is feeling very well but the doctor does not like the look on his face at all. He asks his uncle not to allow visitors for a few days. But the Headman bursts into the scene and wakes up Amal who had fallen asleep. He mocks him with a blank piece of paper saying that here was the King’s letter. Only Gaffer, the Fakir can read it: “I can read quite clearly that the King writes he will come himself to see Amal, with the state physician.” Amal’s uncle does not believe it. The Headman mocks Amal. But soon there is a knocking at the door that grows louder.

The King’s Herald enters to announce that the King will visit Amal in the second watch of the night. Meanwhile, the King had sent the State Physician who comes in and commands that all doors and windows be opened. And he asks Amal, how he feels.

Amal. I feel very well, Doctor, very well. All pain is gone. How fresh and open it is! I can see all the stars now twinkling from the other side of the dark.

Physician. Will you feel well enough to leave your bed with the King when he comes in the middle watches of the night?

Amal. Of course, I’m pining to be out for ever so long. I’ll ask the King to show me the North Star. I must have seen it often, but I don’t know how exactly to locate it in the sky.

Physician. He will tell you everything. [Act II]

The State Physician then asks Amal’s uncle to decorate the room with flowers for the King’s visit. But he points to the Headman and says: “We can’t have that person in here.” The guileless Amal holds no grudges against the Headman who had taunted him and asks that he be allowed to stay. His uncle is keen that Amal asks a boon of the King.

Madhav [Whispering into Amal’s ear] My child, the King loves you. He is coming himself. Beg for a gift from him. You know our humble circumstances.

Amal. Don’t you worry, Uncle.—I’ve made up my mind about it.

Madhav. What is it, my child?

Amal. I shall ask him to make me one of his postmen that I may wander far and wide, delivering his message from door to door.

Madhav [Slapping his forehead] Alas, is that all you will ask for? [Act II]

As Madhav and the Headman discuss what they will offer the King, Amal begins to feel drowsy.

Physician. Now be quiet all of you. Sleep is coming over him. I’ll sit by his pillow; he’s dropping into slumber. Blow out the oil-lamp. Only let the star-light stream in. Hush, he is sleeping.

Madhav [Addressing Gaffer] What are you standing there for like a statue, folding your palms.—I am scared. Are these good omens? Why are they darkening the room? How will star-light help?

Gaffer. Be quiet, unbeliever. [Act II]

There is silence. And then the voice of a child rings out:

“Amal!” Sudha calls. The physician says quietly: “He is asleep.”

Sudha. I have some flowers for him. May I put them into his hand?

Physician. Yes, you may.

Sudha. When will he wake up?

Physician. When the King comes and calls him.

Sudha. Will you whisper a word for me in his ear?

Physician. Of course. What should I say?

Sudha. Tell him Sudha did not forget him. [Act II]

In one deft move, Tagore transforms the play from one about the everyday world of rules and instructions for a sick child to a world where none of these matter. And yet, it is a world that the child and the Fakir had known about all along. And another child honours the dying Amal’s wish to be remembered. Perhaps it was this deep insight into the worldview of children that remains untarnished by worldly desires, accompanied by a yearning for freedom that lies at the heart of the appeal of The Post Office.

The play was performed 105 times in Germany and its theme of liberation from captivity and love for life resonated through all the performances in concentration camps through World War II. The poet Meena Alexander writes of the play’s afterlife:

On July 18, 1942 there was an extraordinary performance—in the Warsaw Ghetto, in an orphanage run by Janusz Korczak, [the Polish-Jewish educator] who put on the play with the children as actors. He said this of his young troupe: “The play is more than a text, it is a mood, it conveys more than emotions, it is an experience . . . and the actors are more than actors, they are children.” Asked why he had chosen Tagore’s play, he is said to have replied: “We must all learn to face the angel of death . . .” Three weeks later, together with the children of the orphanage, he was taken to Treblinka death camp.

[For the full essay see: https://wordswithoutborders.org/read/article/2012-11/translated-lives-rabindranath-tagores-post-office1/]

Tagore died in 1941. His last public speech titled “Crisis in Civilization” reflected on the failures of civilization in the light of World War II. Amal’s story resonates deeply in our war-torn world where too many children are dying.

But beyond the context of World War II, Amal’s story speaks of the wisdom of children who tread the fine line between living and dying.

Indira Chowdhury retired as the founder director of the Centre for Public History (Srishti-Manipal Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore). She teaches and writes about oral history through her website and blog (https://theoralhistorian.com/) She is keen on bringing oral history into the palliative care space.

All quotations from Rabindranath Tagore, The Post Office, Translated into English by Devabrata Mukherjee, New York, Macmillan Book Company, 1914). Quoted here from the digitised version of the Project Gutenberg Ebook 6523, Produced by Eric Eldred and Chetan K. Jain. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/6523/6523-h/6523-h.htm